#stony point penguin colony

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Last Leopard of Hout Bay🦉

The bronze leopard statue on Chapman’s Peak Drive is a well-known landmark, but few know the story behind it. Sculpted by Ivan Mitford-Barberton in 1963, the 295 kg statue was donated to the Hout Bay community as a memorial to the wildlife that once roamed the Cape Peninsula. The project was supported by Pepsi-Cola, which provided the bronze. Over time, exposure to the salty air has caused the statue to turn blue due to oxidation.

According to the Hout Bay Museum, the last recorded sighting of a leopard in Hout Bay was on Little Lion’s Head in 1937. As human settlements expanded, natural habitats shrank, and many species, including leopards, were forced to retreat to less populated areas. Today, leopards are no longer found in Hout Bay, but small populations still exist in the Western Cape's remote mountain ranges.

Despite the loss of their historic range, leopards continue to survive in isolated regions of the Western Cape, particularly in:

- The Cederberg

- The Boland Mountains

- The Overberg, including the Riviersonderend Mountains, Kogelberg Biosphere, and Walker Bay

- The Outeniqua Mountains on the Garden Route

- The Zuurberg Mountains in the Eastern Cape

Leopards in the Western Cape are significantly smaller than their savanna counterparts, and their territories are much larger, often exceeding 100 km² per individual. They are extremely elusive, avoiding human contact and sticking to rugged terrain.

Leopards have been confirmed in the Overberg through camera traps and tracking efforts by conservation groups. However, their presence often goes unnoticed because they move primarily at night.

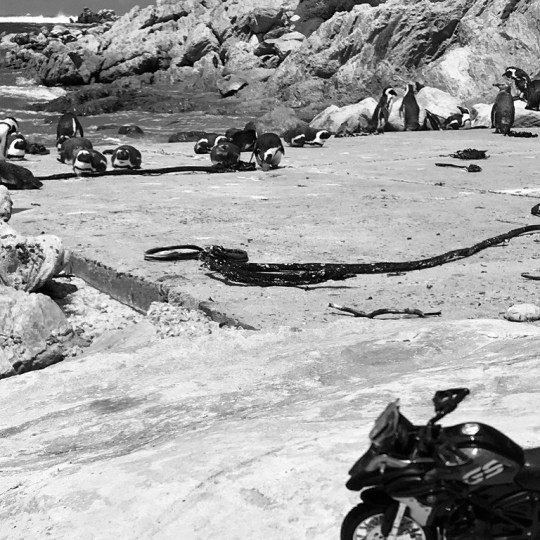

One of the most well-known incidents involving a leopard in the Overberg happened in Betty’s Bay, where a leopard entered the Stony Point African penguin colony and killed over 30 endangered penguins. This highlighted the fact that leopards still roam the region, even in areas where people do not expect them.

The bronze leopard of Hout Bay stands as a permanent reminder of the wildlife that once roamed freely across the Cape Peninsula. Though real leopards have long disappeared from the area, a few still remain in the Western Cape’s remote mountains.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Penguins and Dassies at Stony Point Colony in Betty's Bay (2021-09-18)

Penguins and Dassies at Stony Point Colony in Betty’s Bay (2021-09-18)

View On WordPress

#african penguin#betty&039;s bay#betty&039;s bay penguin colony#kogelberg biosphere#overstrand#penguin colony#penguins#south africa#stony point#stony point nature reserve#stony point penguin colony

0 notes

Photo

#africa #capetown #gardenroute #penguins #stonypointpenguincolony #southafrica #pheniscusdemersus (at Stony Point Penguin Colony) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cedcgn8jV8j/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

18 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Auf dem Weg von Kapstadt nach Hermanus oder umgekehrt lohnt sich ein Stopp in Betty´s Bay und der dort ansässigen Pinguinkolonie. Die gemütliche Kleinstadt liegt unterhalb der Hottentots Berge und war früher für den Walfang bekannt. Überreste aus dieser Zeit sind auch heute noch am "Stony Point" zu sehen. Außerdem ist hier ein kleines Naturschutzreservat, wo man eine Kolonie der Brillenpinguine findet. Ihren Namen haben sie von dem rosa Hautfleck, der vom Schnabel um die Augen geht und aussieht als hätten sie eine Brille auf. Ein schmaler Holzsteg, ca. 300 m lang, führt Besucher durch das Gebiet in dem mehrere interessante Infotafeln aufgestellt sind.

On the way from Cape Town to Hermanus or vice versa, a stop in Betty's Bay and the penguin colony located there is worthwhile. The cozy small town is situated below the Hottentots mountains and was formerly known for whale hunting. Remains from this period can still be seen today at "Stony Point". There is also a small nature reserve here, where you can find a colony of Cape penguins (African penguin). A narrow wooden walkway, approx. 300 m long, leads visitors through the area in which several interesting information boards are placed.

#Betty´s Bay#Stony Point#False Bay#Kapstadt#Cape Town#Garden Route#Penguins#Cape Penguins#Jackass Penguins#Pinguine#african penguin#Südafrika#south africa#Afrika#africa

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Varied second and third days walking the Banks Tracks. Stony Bay was beautiful but New Zealand fur seals owned the beach so swimming was off. Earlier than that day Redcliffe Point was a bracing but scenic place for lunch. Stony Bay had amazing outdoor fire heated baths and predator proof fencing. Flea Bay is home to the largest mainland colony of little blue penguins, mainly living in these cute huts #bankspeninsula #bankstrack #stonybay #fleabay #littlebluepenguin #outdoorbath #redcliffepoint (at Banks Track, New Zealand) https://www.instagram.com/p/CmiVNVALpOj/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Climate change enables Gentoo Penguins to expand their habitat in the Antarctica

New York’s Stony Brook University (SBU) team of researchers were in for a surprise when they spotted gentoo penguin colonies on Andersson Island of Antarctica and also on an archipelago which has remained unexplored and is located off the Antarctica Peninsula’s northern point.

According to a report in smithsonianmag.com, these places are some of the southern-most for gentoo breeding.

Read more

0 notes

Text

Road tripping

Today we would officially start our road trip, but first I had to climb Table Mountain. Willem and I woke at 5am, the crazy storms the evening before had left our plans up in the air, but this morning we woke to perfect weather. We had plans to hike up India Venster before sunrise then proceed up Jacob's Ladder. We met two of Willem's friends at the cable car before beginning our ascent. These guys are regulars on the mountain and I struggled maintaining their pace. After a lengthy battle we arrived. All climbing on Table Mountain is trad climbing, which is a style of rock climbing in which a climber or group of climbers place all gear required to protect against falls, and remove it when a pitch is complete. This would be my first time climbing trad! The climbing was epic and the views were incredible. Ever since I had laid eyes on Table Mountain I had hoped to climb it. Thank you so much Willem and co. for getting me up it!

We said our goodbyes and hit the road, our next destination Kleinmond. It was a beautiful coastal drive with crazy mountainous backdrops. We had big plans to make use of the tent for the first time in South Africa; however, after having a few issues accessing the Kleinmond campground and ominous looking clouds overhead we found ourselves settled into a cosy backpackers looking over Betty's Bay.

The following morning we made a quick stop off at Stony Point to say hello to the penguin colony before proceeding to Montagu. Montagu was recommended to us by our new friend Willem, it turned out to be a climbing Mecca! We were on a tight schedule as I had made plans weeks ago to meet with a climber in Oudtshoorn the following day, which means I was unable to climb. I'm kicking myself that we hadn't planned to stay longer, this is a reason to return though! Montagu is also famous for its hiking, this we were able to fit in. We did a short hike along one of the ridges surrounding Montagu, giving us spectacular views back over the valley. This would be the night we busted out the tent for the first time!

We woke early and hit the road, Google maps informed us that we had a three and a half hour drive ahead us, literally everyone else we spoke to said otherwise, stating it was two to two and a half at max. I assumed google maps was wrong, maybe it was taking in a consideration of incredibly slow drive times along the dirt roads. I was wrong, never assume, the location listed on google maps for De Hoek Mountain Resort is no where near the actual location. Three hours later and a scenic detour over Swartberg Pass, as well as too many kilometres on dirt roads we eventually pulled up at the crag to meet Brendan and Bianca. I was informed by our new friends, that De Hoek was the only limestone crag in South Africa! After the stressful morning it ended up being a very fun afternoon. As we were leaving the crag the clouds were rolling over and the odds of it raining looking more and more likely, we had plans on camping at De Hoek Mountain Resort, when Bianca offered us a bed for the night we were quick to jump at the offer. Bianca lived forty-ish minutes away in the town of George. The drive to George provided us with another crazy beautiful South African sunset. It turned out that Bianca lived in a massive house on a farmstay with lots of animals, the bed was massive and the showers were hot, what more could we ask for! Thank you for being so hospitable Bianca!

Also, a big shout out to everyone who has helped make our trip so amazing, you are all legends!

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Cruising in Antarctica 2020 | JGY Studios Travel Vlog After crossing out 6 continents on our travel bucket list, my wife and I...

#antarctica#antarcticacruise#youtube#whales#leopardseal#penguin#travelvlog#vlog#cruise#travel#iceberg#polarplunge#diving#icesheet#icebreak

0 notes

Text

🔥Antarctic penguin colonies decline by more than 75 per cent in 50 years🔥

The latest headlines in your inbox

Colonies of chinstrap penguins have fallen by more than half across islands in Antarctica, scientists have warned.

Scientists conducting a chinstrap census along the Antarctic Peninsula have discovered drastic declines in many colonies, with some seeing population reductions of up to 77 per cent since they were last surveyed around 50 years ago.

Overall, the number of chinstrap penguins on Elephant Island has fallen by almost 60 per cent, from 122,550 breeding pairs recorded in 1972 to 52,786 today – with climate change thought to be behind the drop.

Researchers from Stony Brook University and Northeastern University in the US joined a Greenpeace expedition to the region, and surveyed chinstrap penguins on the important habitat of Elephant Island.

Chinstrap Penguins on Elephant Island in Antarctic (Greenpeace)

“Such significant declines in penguin numbers suggest that the Southern Ocean’s ecosystem has fundamentally changed in the last 50 years, and that the impacts of this are rippling up the food web to species like chinstrap penguins,” says Heather J. Lynch from Stony Brook University, one of the expedition’s research leads.

“While several factors may have a role to play, all the evidence we have points to climate change as being responsible for the changes we are seeing.”

“There is something broken in the Southern Ocean,” ornithologist Noah Strycker added, a member of the penguin census team.

“Our best guess on why that could be is climate change, which we know is hitting the Antarctic Peninsula region harder than practically anywhere else in the world except the Arctic.”

Numbers of chinstrap penguins have fallen by almost three fifths in half a century in the Antarctic (Greenpeace)

Reduced sea ice and warmer oceans, as a result of climate change, is thought to have led to less krill, the small shrimp-like creatures that the penguins primarily feed on.

The new research has been published after a new record high temperature of 18.3C (64.9F) was reported in Antarctica, beating the former record of 17.5C (63.5F) which was set in March 2015.

Louisa Casson, Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner, said: “Penguins are an iconic species but this new research shows how the climate emergency is decimating their numbers and having far-reaching impacts on wildlife in the most remote corners of Earth.”

And she urged: “2020 is a critical year for our oceans.

“Governments must respond to the science and agree a strong Global Ocean Treaty at the United Nations this spring, that can create a network of ocean sanctuaries to protect marine life and help these creatures adapt to our rapidly changing climate.”

from WordPress https://moosegazette.net/%f0%9f%94%a5antarctic-penguin-colonies-decline-by-more-than-75-per-cent-in-50-years%f0%9f%94%a5/13993/

0 notes

Link

Chinstrap penguins are exquisitely adapted to their environment. They live and breed in some of the world’s harshest conditions, nesting in the windblown, rocky coves of the Antarctic Peninsula, a strip of land comprising the northernmost part of the frigid continent. In water they are precision hunters, darting after krill, the tiny shrimp-like crustaceans that are their sole food source, utilizing barbed tongues engineered for catching the slipperiest of prey. On land, these 2-2.5-foot-tall flightless birds are prodigious mountaineers, able to scale rocky escarpments in spite of their ungainly waddle. Their perfect adaptation to local conditions makes them the ideal barometer for the future of the region. If anything changes in the marine environment, the health of chinstrap penguins will be one of the most reliable indicators. They are the canaries of the Southern Ocean.

And these endearing, black and white emissaries from Antarctic waters are starting to disappear.

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEScientists Noah Strycker and Steven Forrest from Stony Brook University counting penguins on Snow Island in the South Shetlands of Antarctica, on Jan. 31, 2020.

Scientists conducting a chinstrap census along the Antarctic Peninsula have discovered drastic declines in many colonies, with some seeing population reductions of up to 77% since they were last surveyed, about 50 years ago. The independent researchers, who hitched a ride on a Greenpeace expedition to the region, found that every single one of the 32 colonies surveyed on Elephant Island, a major chinstrap outpost, had declined. Overall, the island’s total chinstrap population had dropped by more than half, from 122,550 breeding pairs in 1971 to 52,786 in January 2020. “Such significant declines suggest that the Southern Ocean’s ecosystem is fundamentally changed from 50 years ago, and that the impacts of this are rippling up the food web to species like chinstrap penguins,” says Heather J. Lynch, associate professor of ecology & evolution at Stony Brook University in upstate New York, who designed the study.

“There is something broken in the Southern Ocean,” adds ornithologist Noah Strycker, a member of the penguin census team, and the author of the 2015 book The Thing with Feathers. “Our best guess on why that could be is climate change, which we know is hitting the Antarctic Peninsula region harder than…practically anywhere else in the world except the Arctic.” Warming waters reduce the sea ice and the phytoplankton that krill depend upon for feeding and survival. Ocean acidification, a side effect of increasing global carbon emissions, also impacts their ability to reproduce.

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEA chinstrap penguin nesting at Spigot Peak, in Orne Harbor on the Antarctic peninsula, on Feb. 6, 2020.

For the past five weeks Stony Brook scientists have joined forces with robotics and drone specialists from Boston’s Northeastern University to survey relatively unstudied chinstrap penguin colonies along the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. Chinstraps prefer rocky, windblown sites for nesting, because they provide the best conditions for keeping eggs safe and dry. Those conditions make research difficult: the scientists endured freezing temperatures, wind, rain and snow to reach the coastal rookeries by small inflatable motorboats, then scrambled among the colonies counting penguins by hand. The robotics team backed up the survey with drone footage. When they return to the lab, members of that team will use the findings to teach computers how to identify nests using artificial intelligence for help in future surveys.

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEYang Liu and Vikrant Shah, from North Eastern University, launch a drone from a Greenpeace inflatable. They will later use machine learning to do an automated count of penguin colonies on Elephant Island. The drone counts are later compared to the manual counts done by another team of scientists.

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEScientist Noah Strycker from Stony Brook University Scientist uses a clicker to count chinstrap penguins on Quinton Point, Anvers Island in the Antarctic, on Feb. 4, 2020.

The researchers surveyed 56 colonies in 37 days. So far, they’ve only released numbers from the Elephant Island sites, which were the first to be surveyed. The final report will be published in a few weeks. But those initial findings appear to be consistent across most colonies. “From whatever limited data we have from the 1980s, chinstrap populations appear to be down by over half,” says biologist Steve Forrest, the team lead on the expedition.

On Jan. 31, 2020, 26 days into the expedition, Forrest motored around the President’s Head promontory on Snow Island to scout for potential survey sites. Some 30 years ago, researchers documented a colony there, but Forrest had heard rumors from passing boats that it had disappeared. The sea was too rough for a census that day, but it didn’t matter. Peering through a pair of binoculars, Forrest saw no evidence that there were any penguins left on the island at all. “I was hoping that we might find the colony after all,” he says. “But not finding one is more along the lines of what we expected.” Some of the older surveys in the more difficult-to-reach areas are unreliable — conducted at a distance, by boat — so an exact assessment of how much has changed in the last three decades is impossible. Still, Forrest says, he is confident that chinstrap populations are declining, particularly in the South Shetland Islands (including Elephant Island) off the coast of the Peninsula. “I saw a lot of abandoned nesting places, so I am inclined to believe that it is a real decline, but the precise extent is uncertain.”

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEA chinstrap penguin colony on Elephant Island, Antarctica on Jan. 17, 2020.

While the numbers of chinstraps may be on the wane, the researchers saw a marked increase in gentoo penguin populations. Gentoos, which have red-orange beaks and lack the distinctive black band around the throat that gives chinstraps their names, are much more flexible about what they eat and the conditions under which they breed. This means that they can more easily adapt to changes in their environment. Forrest calls them “climate change winners” for their ability to thrive in conditions that threaten chinstraps— at least in the short term. Strycker calls the process by which the upstarts take over chinstrap areas “gentoofication.”

Strycker, a committed birder who chronicled his attempt to spot more than half the planet’s bird species in a single year in a 2017 book called Birding Without Borders: An Obsession, a Quest, and the Biggest Year in the World admits that ultimately, it’s not even about the penguins. It’s about krill. Krill are the foundation of the marine food system — the fish that eat them are the fodder for the fish on which almost every ocean predator relies. The fish that we humans eat also primarily rely on krill as a food source. If krill populations are unhealthy, it means trouble down the line for everyone else. But krill, in their krillions, are hard to study.

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEthe fluke of a humpback whale at Anvers Island, Antarctica, on Feb. 3, 2020.

Christian Åslund —Greenpeace and TIMEIcebergs outside the coast of Anvers Island in Antarctica.

That’s where the chinstraps come in. Like certain whale species, chinstraps are krill specialists, but they are relatively easier to track compared to whales, with their erratic migration patterns. Chinstrap penguins reliably return to the same rookeries year after year to breed, so by assessing colony health over time, scientists can get a better idea of how the krill they depend on are doing. Which is “why we should care about a bunch of penguins going missing from a remote island that no one’s ever heard of,” says Strycker. “Penguins give us an idea about what is going on in the ocean around us. The ocean processes that are changing in the Antarctic are similar to the processes that are changing everywhere else in the world.” Humans may not have evolved to catch krill the way chinstraps do, but our fate is tied to the tiny crustaceans all the same.

0 notes

Text

There are only a few land-based African Penguin colonies in the world, with South Africa lucky enough to be home to two of these – the first being the famous (and tourist popular) Boulders Beach in Simon’s Town, and the second, the slightly lesser known Stony Point Nature Reserve in Betty’s Bay.

I’m particularly fond of the much quieter but equally as good Stony Point penguin colony, with its beautiful raised boardwalk that snakes through the penguin’s homes and breeding ground.

The compact reserve is home to a colony of African Penguins (who by now are quite acclimatized to the humans peering down at them from above), three species of cormorant (the Crowned cormorant, the Cape cormorant, and the Bank cormorant) that breed on the outer rocks, Harlaub’s Gulls and Kelp Gulls that forage in the colony, as well as a big troop of Rock Hyrax or as we locals like to call them, dassies.

The boardwalk gives you an excellent vantage point from which to watch the penguins go about their daily lives, and come breeding season it is particularly cute to watch the furry youngsters try and strut their stuff!

The colony lies on the site of the old Waaygat Whaling Station which was used to harvest and process whale meat in the early to mid 1900s. Although nearly no remnant of this industry remains in sight, there are plenty of signage boards dotted around in order to give you an idea as to the scale of the whale trade that used to happen here.

Cape Nature manages the nature reserve and there is a lot of very interesting bits and pieces of penguin-related information posted everywhere, making a visit quite educational if you want it to be. (As a bonus, the entrance fee is relatively nominal – making it a much cheaper visit than say a trip through to the comparable Boulder’s Beach.)

Also, there is now a small restaurant built alongside the parking area, useful if you have complaining kids which aren’t all that enamored with the super cute seabird action along with you. Pleasingly, this isn’t us.

We tend to visit this penguin colony at least once a year (more or less), and this year was no different, with Jessica and Emily joining me for a visit to the penguins back in May (all part of our larger day out and about in Rooi Els, Kleinmond and Betty’s Bay).

Pleasingly, for a change the wind stayed away, leaving only perfect weather for us to have to contend with…

The surrounding landscape is quite pretty and there are plenty of opportunities for some great photos to be taken, making a visit to this well managed and relatively quiet nature reserve definitely worth the while!

Related Link: Stony Point Nature Reserve

Stony Point Penguins in Betty’s Bay (2017-05-06) There are only a few land-based African Penguin colonies in the world, with South Africa lucky enough to be home to two of these - the first being the famous (and tourist popular)

#african penguin#betty&039;s bay#boardwalk#cape nature#nature reserve#penguin colony#rondevlei lake#south africa#stony point#stony point nature reserve#stony point penguin colony

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lots of penguins 🐧 in Africa 🇿🇦. @snapon_official @amsoilinc @jesseluggage @sanuk @spot_llc @schuberthelmet @moto_skiveez @traverse_magazine @quadlockmoto #snapon #AMSOIL #TeamAMSOIL #jesseluggage #smilepassiton #motoskiveez #quadlock #findmespot #adventureawaits #getloststayfound #leucadia #advrider #adventurebikeriders #motoadventure #dualsport #mototravel #travelwriter #mototrip #travel #bmw #overland #bmwgs #adventure #motorcycle #dualsport #instamoto #bmwmotorrad #advmoto #penguins #hermanus #capetown (at Stony Point Penguin Colony) https://www.instagram.com/p/B4-b7hiHyqm/?igshid=12samp20uveat

#snapon#amsoil#teamamsoil#jesseluggage#smilepassiton#motoskiveez#quadlock#findmespot#adventureawaits#getloststayfound#leucadia#advrider#adventurebikeriders#motoadventure#dualsport#mototravel#travelwriter#mototrip#travel#bmw#overland#bmwgs#adventure#motorcycle#instamoto#bmwmotorrad#advmoto#penguins#hermanus#capetown

0 notes

Text

The Great White Hope: Notes from Antarctica, Earth’s Last Great Wilderness

In Antarctica, the writer finds promise, peril, and nature so grand it inspires poetry.

Gentoo penguins fling themselves from an iceberg into frigid Antarctic waters. Photo: Cotton Coulson and Sisse Brimberg

The riotous seas of the Drake Passage—one of the world’s most treacherous stretches of water—lie down for us as we cross, aboard the ship National Geographic Explorer, in a spell of good weather. We sailed from the world’s southernmost city, Ushuaia, Argentina, for the closest part of the cold continent, the Antarctic Peninsula, escorted by petrels and albatrosses. All are graceful on the wing, but the birds that draw my eye are the wandering albatrosses. Greatest of seabirds with their 11-foot wingspans, wandering albatrosses are masters of dynamic soaring. I watch them course effortlessly on set wings, tacking in wide turns, their wing tips narrowly clearing the swells. Now and again an albatross glides parallel with the ship’s gym, glancing in the windows at passengers labouring on treadmills—and inspiring my new stanza for Samuel Coleridge’s 1798 poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” in which an ill-fated ship is driven by winds toward the cold continent: At length did cross an albatross, Which our treadmills and ellipticals, Free weights and rowers, Nautilus And NordicTrack just could not outpull.

Not great poetry, maybe, but new stanzas seem in order, for we’re headed to a land in transformation—a new Antarctica.

“The ice was here, the ice was there, the ice was all around,” Coleridge wrote as his mariner sailed for the South Pole. Alas, there is much less ice now. Antarctica remains Earth’s last great wilderness, but global warming is bringing rapid change. The Antarctica of the next millennium is taking shape. I’ve come for an early look—and to connect with nature on a scale I have rarely seen.

A day and a half after departing Ushuaia, we’re approaching the South Shetland Islands, volcanic outliers of the Antarctic Peninsula. As we near land, we smell it before we see its point of origin—a sudden strong odour of ammonia. At the deck rail, I look for some duct behind me, assuming the smell is venting from the bowels of the ship. But the wind is off the beam. A fellow passenger and I exchange glances of wild surmise. Then, “Penguins!” she cries, pointing. The smell is wafting from a penguin rookery, my first intimation of the crazy abundance of life in Antarctica—and its assault on all of the senses.

Our ship turns in for Barrientos Island, in the middle of the South Shetlands. We coast by its cliffs of columnar black basalt. Soon we drop anchor and board the ship’s inflatable Zodiac boats to visit rookeries of gentoo and chinstrap penguins—following our noses, in effect. The gentoo, a six-kilo bird, takes the low land here. Four-kilo chinstraps are the highlanders, gathering densely atop rock outcroppings. This choice, to me, seems almost religious. Perched on stony altars—a little closer to heaven—and waggling, the birds direct their beaks up and cry out piercing hosannas. As the frenzy dies down, the beaks drop, pointing to more earthly chores: grooming feathers and feeding chicks.

Passengers from the National Geographic Explorer pole their way up to a penguin colony at Orne Harbour. Photo: Cotton Coulson and Sisse Brimberg

My fellow passengers are as excited by all this as I am. Linda MacGregor, our most elegant dresser in the evenings, plops down in her rain pants near a gentoo nursery and grins as a moulting chick clambers toward her. The chick seems to expect her to regurgitate some krill. Had Mrs. MacGregor been able to, I believe she would have. Jann Johnson, from California, stands among the penguins, incredulous. “I know I’m here, but I don’t believe I’m here,” she exclaims to no one in particular. “It’s beyond all dreams.” As she says this, her boots are becoming smeared with guano and mud, possible contaminants that Explorer neutralizes with a battery of shipboard brushes, disinfectants, and jets of hot water. We use these both when embarking and disembarking, determined to neither export contagion to this frozen world nor import it to the ship.

***

Our expedition leader, Tom Ritchie, is as Antarctic explorers are supposed to be, ruddy and bearded. A throwback to Victorian naturalists such as Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, he is a generalist, free to follow his curiosity wherever it leads. Picking up a fur seal femur on the beach, he tells me it came from a juvenile, noting the unfused epiphyses at either end of the shaft. Then, hefting the skull, he adds that the juvenile was a male. Ritchie discourses on Antarctic fauna—such as it is—as easily as on botany, meteorology, geology, and ornithology.

“I’ve been coming to Antarctica for more than 30 years,” he notes. “It’s in my blood. The human history here is fascinating, the natural history like nowhere else on Earth. This is just a very dynamic place—and in some respects a dangerous, sinister place too.”

Could he be referring to the destruction humankind wrought on this remote ecosystem in the first half of the 20th century—the unchecked slaughter of whales in these southern waters, which nearly extinguished the blue whale and brutally reduced populations of the smaller krill-eating baleen whales? Antarctic wildlife is still in flux from those days. The slaughter of the whales triggered explosions in populations of other krill eaters, especially the crabeater seal, now one of the most numerous large mammals on the planet. This huge disruption of nature foreshadowed the potentially larger disturbance now being visited on Antarctica by climate variations.

Two humpback whales lure passengers to the ship’s rail for a close encounter. Photo: Cotton Coulson and Sisse Brimberg

As our ship works its way down the peninsula, Antarctica’s dynamism is evident everywhere. It’s in the weather, of course, which is big and volatile. It’s in the way the stark, lifeless interior meets Antarctic waters teeming with life. It’s in the juxtaposition of glaciers with volcanic formations and geothermal steam—the marriage of ice and fire. It’s also evident, more subtly, in the way ruins of human enterprise—an abandoned Argentine refugio shack, the tumbled stones of a rude, French-built meteorological lab—accentuate the vastness of the wilderness beyond.

I see little dynamism, at first, in the colours of this frozen landscape. The basic palette is the grey-black of exposed rock and the white of ice and snow. Many creatures I spot echo this grey-black white tonality, from the penguins to seagulls, seals, and killer whales. But my eye wants colour and trains itself to find it, zeroing in on the blue light glowing in glacial ice, the green of moss, the red in gentoo beaks, the orange caruncles on the face of the blue-eyed cormorant—and the lunatic cobalt of its iris. The colours here seem to live; each hue is all the warmer and more luminous for its black-and-white context.

There is, too, the temporary dynamic that Explorer brought here and would take away when we sailed: the sharp discontinuity between our life on and off board. On board are the staterooms, gift shop, fully stocked bar, and “wellness” area. Off board is infinite Antarctica, windswept, cold, alien.

At the head of Charcot Bay, on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula, we spend a morning cruising Lindblad Cove in rafts as snow falls. The margins of the cove blur in mist that thins occasionally for glimpses of the surrounding peaks—bold ramparts of dark rock with steep couloirs and hanging glaciers. Our rafts proceed slowly, searching out passages through a maze of slush ice, ice floes, small icebergs, and giant tabular bergs that would have dwarfed the Titanic. Several fur seals have hauled out on their own floes. One grows enormous as we approach, resolving itself into a huge female leopard seal, 11 feet long.

“Dangerous” and “sinister” Tom Ritchie had said of Antarctica, and here, in this sleek avatar of an extraordinary continent, I find a creature worthy of the adjectives. The skull, reptilian in its contours, with a thin black line marking the wrap-around mouth, reminds me of a death’s-head mask. As I watch her, the seal yawns, and I’m startled by her immense gape. Her fanged mouth opens to nearly 90 degrees.

Photo: Cotton Coulson and Sisse Brimberg

“Don’t change your lenses outdoors,” said photographer Cotton Coulson. “You never want to get moisture or condensation inside the camera body. Put your cameras and lenses into a plastic bag and seal them up before you bring them indoors. Once inside, place them in the coldest area you can find so they slowly warm up to the new temperature.”

(function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5&appId=440470606060560"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

from Cheapr Travels https://ift.tt/2N0CQub via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Happy South African Penguins #southafrica #penguins #stonypoint #animals #nikon #penguincolony (presso Stony Point Penguin Colony) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bt3jInFlre8/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1wsal1zp560i9

0 notes